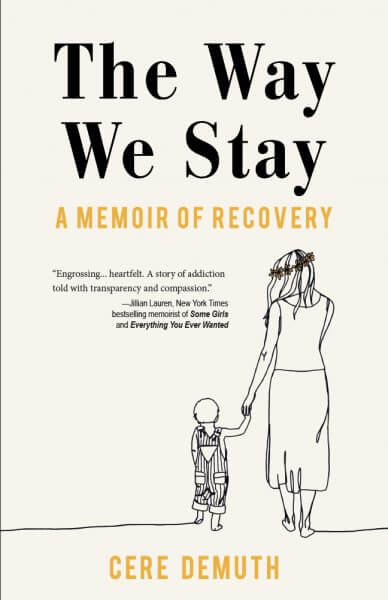

Introducing: The Way We Stay by Cere Demuth

Cere’s only son’s opiate addiction leaves her coping with pain, fear, and humiliation for twelve long years. A small town psychotherapist, living in the idyllic islands of the Pacific Northwest, she struggles to balance the needs of her family beneath the shadow of addiction. She revisits her tumultuous childhood beginning in the Bay Area with her birth during the Summer Of Love to leftist radical hippies. Cere retraces her parents’intense, but brief, political involvement in the leftist militant group, The Weather Underground. Eventually, her family moves to Whidbey Island where her parents raise her and her brother in a small, rural, alternative community.

In the midst of a painful, high-risk, adolescence she invites the reader into her internal world as a teenage mother in 1985, an adoptive mom in 2000, and a psychotherapist of twenty-five years desperately trying to heal her family and herself from the suffering caused by addiction. Written in a sparse, poetic language, The Way We Stay is a story of heartbreaking love, vulnerability, faith, and healing.

Buy a copy now. Affiliate link

Excerpt from The Way We Stay by Cere DeMuth

I say the Serenity Prayer.

I put Stacy and Nate in God’s hands.

I pray for the next right thing to happen.

I breathe.

I feel an undeniable amount of pressure and blame. I feel isolated, alone and misunderstood. At the grocery store, I sit in the car preparing myself to see all the people who I know and who know me. Everywhere, I see my friends, acquaintances, colleagues, clients, and friends of Nate’s.

My heart races, I dig deep for my dignity and courage. I struggle with what to say. I want to tell the truth, but without betraying my own boundaries and privacy. I cannot not say I am fine, or we are fine. Nothing is fine. I am isolated in a world of addiction. I fear every day for the life of my son, the safety of my daughter-in-law and my grandsons.

I wonder when I am not there if they have food in their fridge. Did Stacy have to go to the food bank at Good Cheer? When Nate is home I wonder if he is ignoring the boys. He usually is. Is he driving them around high? Is he going to get pulled over for not having a license? Will they end up in foster care? I worry about the trauma and stress the boys and Stacy are living with and what kind of chaos Nate is leaving in his wake.

At the grocery store, when I walk through town, sitting with clients, this is what I think about. I am in pain every moment. I feel judged, misunderstood, and exposed. I do my best to tell the truth.

I say, it’s hard.

Nate struggles with addiction.

The boys are good.

Stacy is an amazing mom.

I see them every week.

I’m lucky.

These are the things I say.

I feel like throwing up.

I hold my breath.

I feel disconnected, alone and terrified. I want to hide. I am tired of being strong. I am tired of being brave. I want to retreat into a fetal position until its all over, until he is better, or dead.

I can barely breathe.

I pack my groceries in my, oh so perfect, five pack of reusable floral grocery bags and head to the car. I unload the cart. I return the cart. I get in my car. I turn it on. I put on my country station, take a deep breath and try desperately to feel okay. It’s as if I have just come through a horrible storm and barely escaped with my life. Every time.

I tell myself again, it’s not your fault.

Yes, you made mistakes.

All moms make mistakes.

Focus on what you can do right now.

You can go home, unpack the groceries.

Make some good food.

Read books to Vida.

Play with Vida.

Go for a walk.

Cere, you need to focus.

Focus on what is good and beautiful and right in your life.

Give those things more energy, more time, more weight.

Let go of the negative.

Let go of the addiction.

It’s not yours to fix.

I pray.

I put Nate in God’s hands, he falls out, I do this over and over again as I drive the mile down Lampard. By the time I arrive home, I am less about to curl up in a fetal position and more ready to play with Vida, unload groceries and make dinner. I am temporarily at peace.

This is what my trips to the grocery store are like for twelve long years, over a thousand trips to the grocery store in this small town, on this small island. Each trip is full of shame, fear, vulnerability, and then recovery. I don’t think anyone knows how truly awful I feel. But, I do.

The worst people to see are the parents of Nate’s friends. The parents whose kids are doing well. They are in college. They are moving forward in life. They aren’t addicted to oxycontin or heroin.

The best people to see are the ones who are living like me. The other ones in fear every day for their child’s life because of addiction. They are like a beacon of light. We see each other, really see each other, and recognize the suffering. It is rare, though, to see those moms, and those dads, because they are hiding too.

There is one person I look forward to seeing. I usually run into her once a month, in the morning, in the produce section. Her daughter and son-in-law were once in that oxycontin world with Nate. They are clean now. As a mother and grandmother she has been through the worst and she is on the other side. When I see her my hope is renewed. We embrace. I feel understood and less alone, briefly.

I don’t want to tell anyone, it’s not just the painkillers, it’s not just oxycontin, now it’s heroin. Everyone knows heroin is the worst, the dirtiest most shameful drug that anyone does. Even when my clients talk about people they know on drugs they say, at least it’s not heroin. People die of heroin overdoses more than any other drug.

Terror moves through every ounce of my body. My heart beats like a train barreling down the tracks. My gut feels as if a hundred pound weight has been dropped inside.

I can’t get rid of this pressure, this ache, this life that is being contaminated by addiction. I can’t protect Nate. I can’t protect Stacy. I can’t protect those blond haired blue-eyed boys I love so much. I can’t even protect myself.

It eats me up, every day.

It’s as if a shard of glass is wedged deep in my foot that will never come out. Every step I take the pain permeates my body, some days more than others, but always, always it aches. There is never a moment that I am unaware of the pain. There is no relief.

To survive, I do what I have taught myself to do over the years when these same overwhelming feelings of panic, pain, fear, powerless, and grief wash over me, I pray. Not because I have so much faith in God, but because to survive I have to believe there is some power greater than myself. I have to believe that in some way that a higher power can relieve my suffering if only for a second. If it can relieve mine, just maybe it can relieve Nate’s, too.

Buy a copy from our Amazon Store.

This is an affiliate link.</p