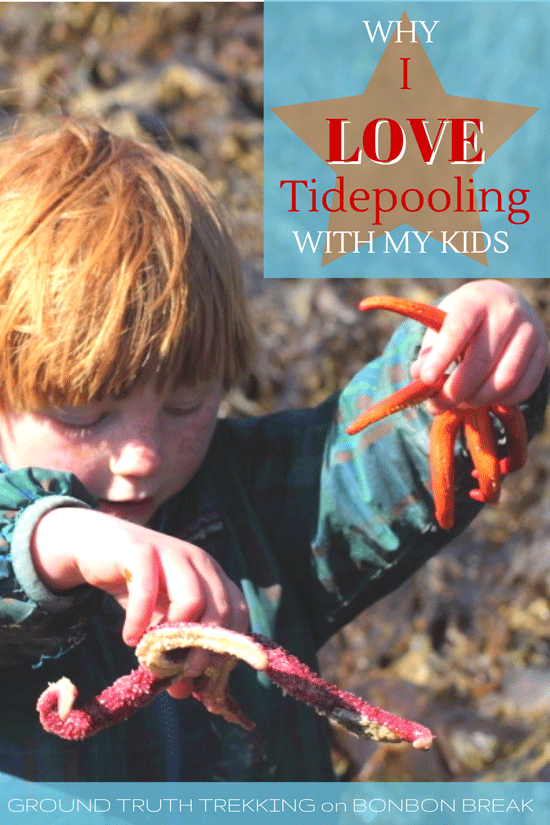

Why I Love Tide Pooling with my Kids

By Erin from Ground Truth Trekking

I scanned the column of green numbers on the July page of the tide book: Sunday the 13th, 9:52AM, -5.4 feet

-5.4! A number for boots skating through a knee-deep tangle of kelp blades. For rocks so covered in life that there’s not an inch of rock left on them. For all that scuttling color and slimy blobbyness.

I know of course, that intertidal creatures are my own addiction. They’ve had a special place in my heart since 10th grade marine science class, where I memorized their scientific names from a thick stack of hand-illustrated 3×5 notecards.Strongylocentrotus drobachiensis. Tonicella lineata. Pisaster ocraceous. Hemigrapsus nudus. A few still pop to mind, nearly twenty years later–are still relevant even, 1500 miles away along the same convoluted Pacific coast.

But I can say I do it for the kids. I gulped a few hot sips from my thermos bottle of coffee then hooked it over a finger that held a shovel, on an arm that held an empty bucket, and held Lituya’s hand as we slithered our boots carefully over the ropes and sheets of seaweed that draped the cobbles, in the ankle-deep water pouring out through the spit, to a sand flat just barely beginning to be revealed.

Drinking coffee while low-tiding is basically the point of this whole new-found tradition of camping out around every full moon. In the half of the year that stretches between the spring and fall equinoxes, the lowest tides of the month are always paired with the full moon, and are always, in my neck of the woods, somewhere around 9 or 10 in the morning. I’ve drawn misshapen circles and squiggly orbit lines on the white board, and never quite managed to explain quite why it works out that way. But I know when to head to the sea.

Leave all our heaps of clothes and sleeping bags in the tent and we can stroll down the beach to beat the morning’s tide by an hour, easy. And that’s even after a breakfast of squashed peanut butter sandwiches and a fight with the five year old over whether he had to wear his rainpants (he won).

“An anemone!” Lituya squealed. “Can I touch it!”

“Yes, of course.”

“Look! It’s circle got smaller! Why is it scared of me?”

I stopped my hurried splash past all the commonest things–the true stars and burrowing anemones and hairy tritons–to crouch down with her, feeling the tacky pull of tentacles and tube feet, running our fingers over the sandy worm cases on the cobbles and their little tubes poking out of the flats. Gooey, sandy, slimy, sharp, rough, hairy, sticky, spongy, slippery, wiggly, spiny, soft, and wet… Low tide is for touching.

Low tide has a sound. A hissing squealing whistling popping–of water disappearing, of barnacles closing, of limpets and snails suctioning their moist bodies down against the rocks. Katmai and I watched finger-length fish dart by dressed in kelpy red-brown and sand-speckled gray. Then a small giant octopus streaked past our feet like a dark red rocket, crawling when the water got too shallow. We caught it for a moment in our white bucket, watching it turn paler and paler as if trying to become the bucket itself. Then we let it go.

We let them all go. The octopus, the dime-sized sea urchins, the flapping gunnel fish and gliding nudibranchs and the seven common kinds of crabs we know.

Low-tiding isn’t a useful obsession, as I like to claim for the dozens of gallons of berries I pick, or the buckets and bowls full of salad from the garden. We came back this time with a heap of nori to dry for snacks. Sometimes with clams. More often with pictures, or nothing at all.

I’ve forgotten most of those latin names. I don’t know as much about each creature as a naturalist. I can’t catch a gunnel fish like a Seldovia child.

But I love the lowest tides. A treasure hunt for the colorful, slimy, and strange–for all the things that hide beneath the rocks and scuttle into damp dark crevices. Even the abbreviated nature of it–a mesmerizing exploration of a few square feet, followed by a mad scrambling dash when the water rises to the tops of my XtraTufs and chases me up the beach almost before I know it’s coming (and maybe over the tops, if I’ve left myself out on a sand flat). The letting-go ritual, where the kids sit near the water’s edge, with the water lapping at their cuffs and boots and they don’t even notice, reaching into the bucket and throwing everything back. We can see this much of the sea for only a few hours a month–precious and special in its rarity.

When the sunflower stars glide around my feet, first curling and uncurling one arm, then another, their delicate tube feet tapping the seaweed in a rapid searching crawl–it’s like watching my children playing together when they don’t know I’m peeking. A glimpse into the magic of a world that doesn’t include me.

READ A LITTLE MORE FROM ERIN’S SITE:

ABOUT Erin: You’ll find me in a yurt in a little village in Alaska, where I live with my husband and two young kids (3 and 5 years old). More likely, you’ll find me outside of it, picking berries, growing cabbages, coaxing small children along wilderness trails, and loosely supervising all their tree-climbing, rock scrambling, ocean splashing adventures. Sometimes, you’ll find me very far outside of it indeed, traveling with my family on months-long expeditions in the Alaska wilderness. I am a writer, and the author of two books on these adventures: A Long Trek Home: 4,000 Miles by Boot, Raft and Ski, and Small Feet, Big Land: Adventure, Home and Family on the Edge of Alaska.

ABOUT Erin: You’ll find me in a yurt in a little village in Alaska, where I live with my husband and two young kids (3 and 5 years old). More likely, you’ll find me outside of it, picking berries, growing cabbages, coaxing small children along wilderness trails, and loosely supervising all their tree-climbing, rock scrambling, ocean splashing adventures. Sometimes, you’ll find me very far outside of it indeed, traveling with my family on months-long expeditions in the Alaska wilderness. I am a writer, and the author of two books on these adventures: A Long Trek Home: 4,000 Miles by Boot, Raft and Ski, and Small Feet, Big Land: Adventure, Home and Family on the Edge of Alaska.

Follow Erin on Facebook | Twitter | Pinterest |Google+

CONTINUE READING IN THE BACKYARD

![]()